Urban Runoff Cure: Making Cities REALLY Green

In urban areas, a good rain leaves the streets cleaner, with dust, oil and small debris swept away. But that’s only an appearance, because what’s swept off the pavements is now not just water, it’s “runoff.” All the chemicals deposited on those surfaces between rains – fuel, oil and tire dust from cars and trucks, carelessly discarded toxic trash, chemicals leached from treated surfaces — all have been flushed into the surrounding rivers, lakes, estuaries and bays. Almost all the rain that falls on vast shopping centers with many acres of impermeable surface covering roofs and parking lots pours into the local sewers and waterways.

In urban areas, a good rain leaves the streets cleaner, with dust, oil and small debris swept away. But that’s only an appearance, because what’s swept off the pavements is now not just water, it’s “runoff.” All the chemicals deposited on those surfaces between rains – fuel, oil and tire dust from cars and trucks, carelessly discarded toxic trash, chemicals leached from treated surfaces — all have been flushed into the surrounding rivers, lakes, estuaries and bays. Almost all the rain that falls on vast shopping centers with many acres of impermeable surface covering roofs and parking lots pours into the local sewers and waterways.

The Pembroke Mall with its 700,000 square feet of roofs and thousands more of parking places pours millions of gallons of tainted water directly into the Virginia Beach network of estuaries that flow into Chesapeake Bay. But it is only one of the many sources of runoff that have virtually destroyed the oyster beds and fishing in that once prolific body of water.

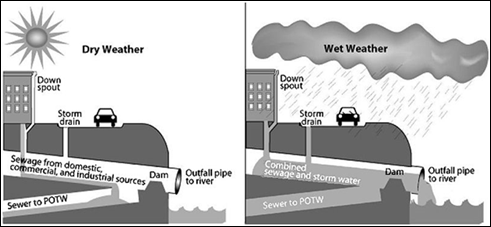

Runoff is a particularly serious problem for cities that have combined sewers. Normally the sewers just carry sewage: cooking, washing, toilet and industrial effluvia which in modern cities flows along the bottom of sewer pipes directly to sewage treatment plants. But when there’s a good rain, all that water pours off the roofs and streets and sidewalks into the street drains and into those same pipes where the sewage flows, mixing it up. If there is enough water from the rain to fill the pipe, it goes into the overflow pipe, which delivers it, raw sewage, rainwater and all, directly into the nearest waterway. New York City, which has strived to be one of America’s greener cities, still dumps sewage-laced water into the Hudson River during heavy-rain events.

Controlling urban runoff means transforming a substantial part of an entire city or town, changing its impervious surfaces into water-holding, water absorbing and water-filtering areas. Philadelphia is prepared to spend (so far) two billion dollars over 25 years doing just that, and its plans include all of the above. Large industrial buildings will literally sprout green roofs that will hold the rain that falls on them instead of dumping it down the roof drain. Some of the water that falls on those roofs will nurture the plants that grow on them, the rest will evaporate over time. When there are enough of them, a side benefit of green roofs is better air and less CO2, as plants absorb the latter.

Controlling urban runoff means transforming a substantial part of an entire city or town, changing its impervious surfaces into water-holding, water absorbing and water-filtering areas. Philadelphia is prepared to spend (so far) two billion dollars over 25 years doing just that, and its plans include all of the above. Large industrial buildings will literally sprout green roofs that will hold the rain that falls on them instead of dumping it down the roof drain. Some of the water that falls on those roofs will nurture the plants that grow on them, the rest will evaporate over time. When there are enough of them, a side benefit of green roofs is better air and less CO2, as plants absorb the latter.

Philadelphia plans to repave streets as they require replacement with porous asphalt surfaces that are engineered to let the water that falls on them percolate through to the earth underneath rather than pour into the sewers. The moisture collected that does not flow to plantings on the street’s periphery will gradually evaporate back through the surface. Porous streets are still experimental in that it is not known how, of if, the pores will fill over time, leaving the street impermeable again.

The use of swales is another method of capturing runoff that is going to change the ecology of the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. In nature, swales are marshy depressions that capture and contain water. In an urban context, swales are gardened areas that run along the sides of streets, often between streets and sidewalks, but slightly below the surface of the street. When it rains, they absorb and hold local runoff, preventing it from entering the sewer system. The Gowanus Canal, used as an industrial dump for generations, has also spent those generations as the recipient of the area’s storm water runoff, sewage included. It is expected that the 45,000 square feet of swales planned for the area will cut its rainwater runoff radically, preventing sewage from entering the canal in all but the heaviest rain events.

It would seem that green lawns running to the edge of lakes would be innocent of contributing to runoff, but that isn’t so. In a light rain, established turf grass absorbs water nicely, but in a heavy rain, turf grass quickly saturates and the rain slides off and into the lake, taking some of the fertilizers and pesticides that our lawn-obsessed culture requires to keep the lawn green and weed-free. This is ironic, considering the fact that in most sub-urban areas, as much as 45% of the water demand is attributed to outdoor use, most of it for watering lawns. Turf grass needs and likes a lot of water, but after a short period of heavy rain it stops absorbing water and becomes a source of runoff.

As part of the effort to restore Chesapeake Bay, communities like Virginia Beach, which have many green-lawned homes bordering the estuaries that feed Chesapeake Bay, are encouraging residents to replace their lawns with plantings that will absorb the rains. At the least, they are asking residents to border their lawns with swales of deep-rooted plants that will catch rain runoff before it reaches the waterways.